Lucy Connolly: Legal Defence (Part II)

In Part I, I make the case that Lucy Connolly was systematically goaded into tweeting what she did. I am adamant indeed that the post which falsely identified the Southport attacker as an asylum seeker emanated from a government-run account.

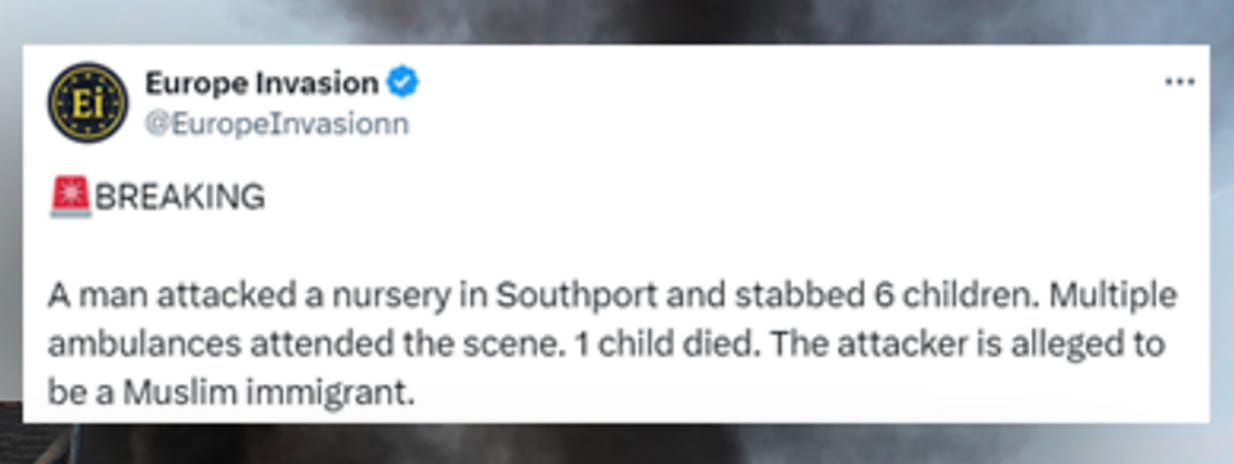

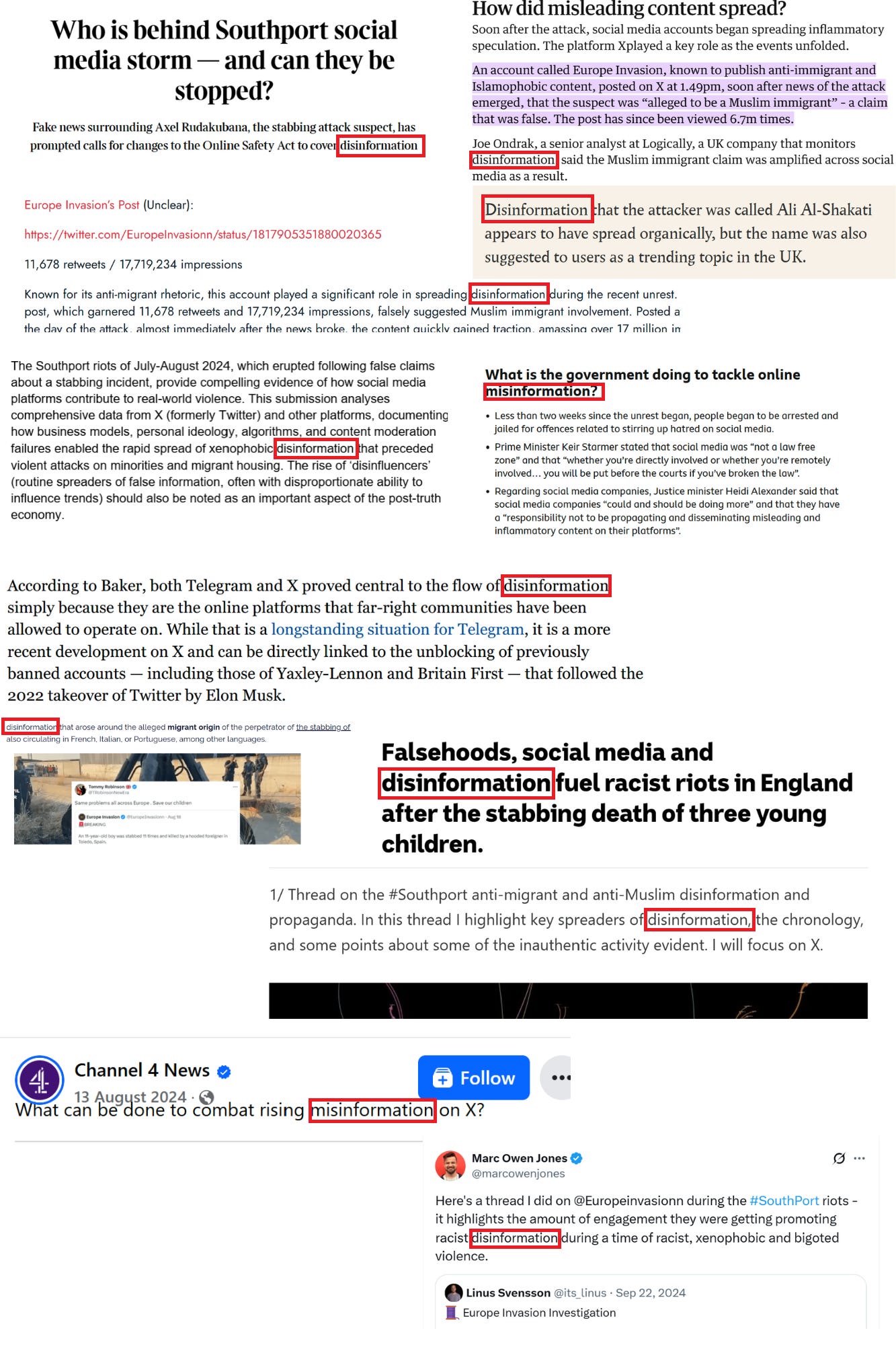

It is the gratuitous shoehorning of “confirmed to be Muslim” and “alleged to be a Muslim immigrant” in both tweets which makes anyone angrily reacting to the post liable to be accused of “racial hatred”. It is the syntax, which does not ring true and bears the Nudge Unit’s fingerprints. It is the dry, flipchart-derived name of the account - “European Invasion” - which conforms to a style used by a number of state-conceived entities that have materialised out of thin air in recent years, all with no apparent provenance. Above all, though, it is the uniformity of the media coverage that immediately follows. This involves pummelling you with the term “disinformation” or “misinformation” over and over and over, à la Operation Mockingbird, with Europe Invasion’s post serving as the all-needed citation.

Nothing is more revealing of a psy-op than the legislative subtext found in the media coverage after the fact; and so this makes for a general rule: wait to see what they want out of an event. The problem-reaction-solution formula invariably becomes readily apparent. On prior occasions, it was the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. Then, the Public Order Bill. In this case, calls for beefing up the Online Safety Act 2023 were being made before Lucy had even set foot in a police interview room. Keep in mind, they will always overshoot when it comes to introducing totalitarian laws by asking for more than they want. That way, when a provision of a particular bill is subsequently amended or removed, it will made to feel like a climbdown, all thanks to the hard work of your favourite civil liberties campaigners, “Big Brother Watch” (who are in on the whole charade). Of course, it’s an entirely Pyrrhic victory that will have been secured and what you consider a climbdown will have in fact been war-gamed in from the beginning. If you’re really lucky, they may even let one of your silly, little petitions reach a 100,000 signatures, earning you a precious “debate”. All the while, the veneer of democracy is sustained.

Back to the matter in hand, the tone of the coverage was clear: the scourge of “disinformation” needed to be addressed, pronto. So we mete out a string of custodial sentences for “hate speech” in quick succession, Lucy’s among them, before ushering in the new OFCOM regulations on so-called “illegal content”, effective March 2025. Note, the regulations are lucrative business. Breaches come with very heavy fines, up to 10% of the offending platform’s global turnover. That’s turnover, not profit. For a platform like X, we are talking up to £400 billion, none of which, by the way, is earmarked for so-called “online safety”. It goes straight to the treasury. I would tentatively surmise, in fact, installing the regulations was much more to do with taxation through the back door by means of hefty fines than actual censorship. After all, they need “illegal content” to persist in order to levy the fines, all the while paying lip service to protecting you from ‘online harms’.

As confident as I am that Lucy was set up by 77th Brigade, I concede I cannot prove it. I can only claim to have become a keen observer of how numerous psy-ops have have played out, in the last five years especially. With that, comes an acute familiarity for the various tell-tale signs discussed. Whether you are persuaded by these signs is a matter for you. Ultimately it will come down to whether you believe the state is sufficiently devious, capable and motivated to pull off a straightforward exercise of this kind. Means, motive and opportunity (MMO), in other words. For the purposes of this piece, however, it is not what I have to prove, but rather what the Crown has to prove that concerns us. This brings me to her legal defence, that of which she was ultimately deprived.

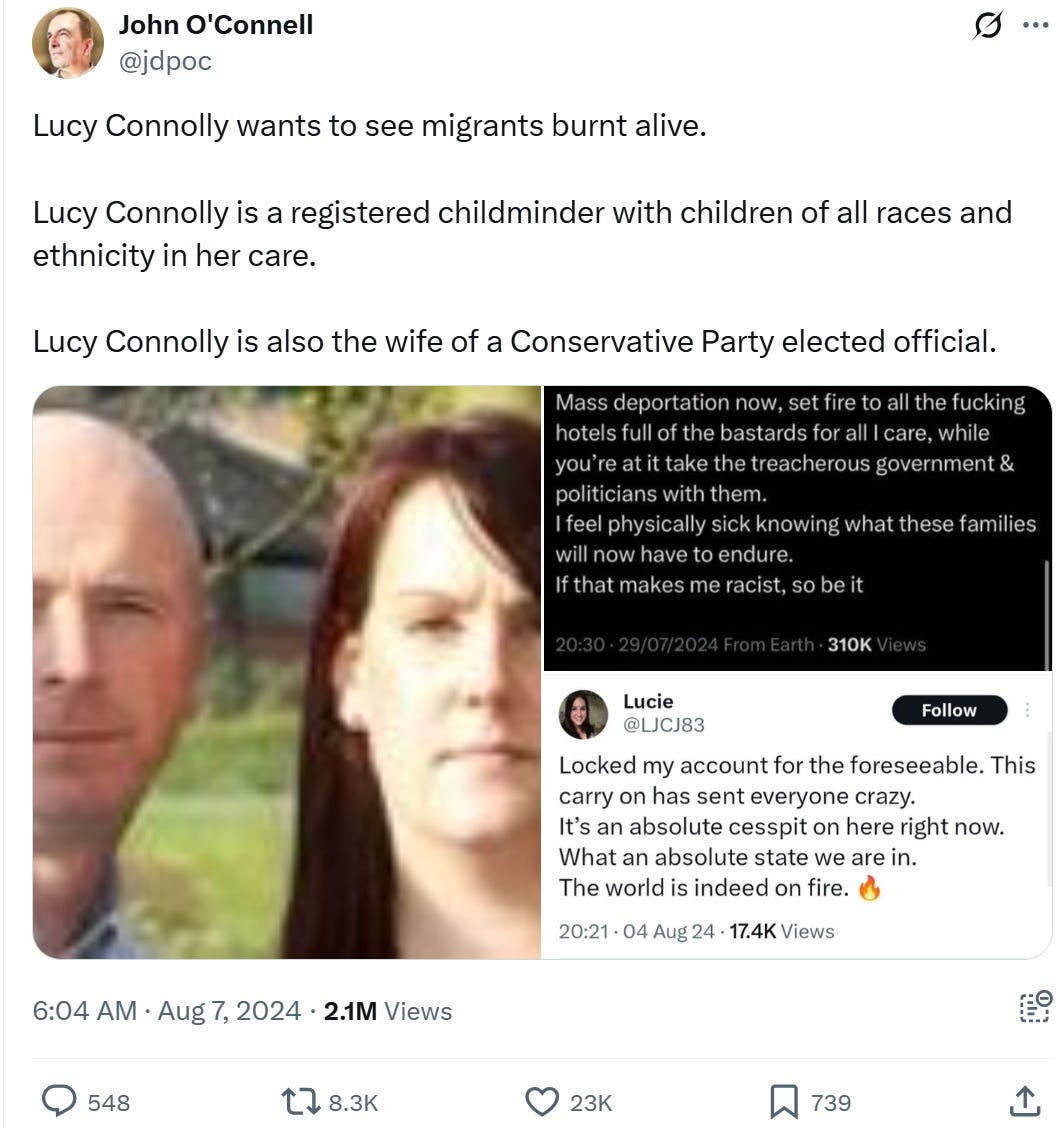

Before one gets to the question of what she posted, Lucy’s prospects of receiving a fair trial were shot. There was a deluge of reporting all aimed at drumming up support for regulating social media platforms, all of which had the so-called “far right” in its crosshairs. Several pieces were juxtaposing the Southport riots with Lucy’s post or similar rhetoric as to link A and B. Needless to say, an aggressive censorship initiative was underway and, in line with that, it was clear those who had transgressed accepted norms of online chatter needed to be made examples of. More than that, several accounts were seen discussing her tweet whilst she was still on remand, mischaracterising her words and omitting to mention that the tweet had been deleted. The deletion is crucial to any eventual defence Lucy might hope to enter as it goes it to intent. There is a world of difference between someone who posts something intemperately, then thinks better of it and hastily deletes it, versus a legitimate attempt to foment unrest. It corrupts the perception of any reader to suggest Lucy was in anything other than the first category. The example below, dated 7th August (with 2.1 million views) is particularly egregious in that he states in the present tense that the Lucy “wants to see migrants burnt alive”. These are all grounds for her legal team, such as it is, to put in a stay of proceedings application yet none is made.

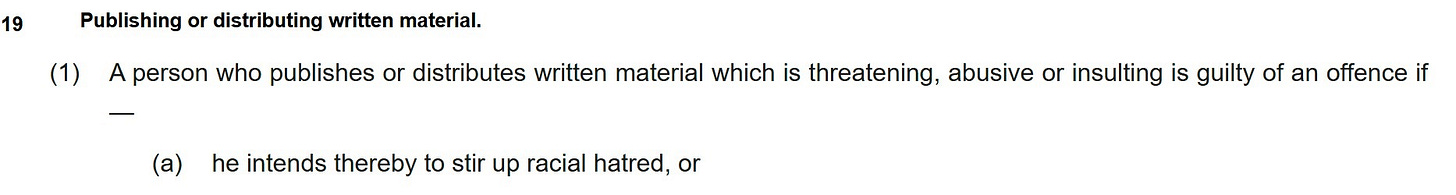

I now turn to defending the charge proper. Under section 19(1)(a) of the Public Order Act 1986, the prosecution is required to prove beyond reasonable doubt that: (i) the Defendant published or distributed written material; (ii) the material was threatening, abusive or insulting; and (iii) the Defendant thereby intended to stir up racial hatred.

No “racial hatred”

The deleted post contains no discernible target group by reference to “colour, race, nationality (including citizenship) or ethnic or other national origins” as exhaustively defined under s.17 of the Act. Race simply does not feature in the defendant’s post, not even incidentally. There are no racist slurs or racist tropes. The post is not a racist diatribe. There is no racist innuendo. There is no dog-whistle reference to any race, no nod and a wink. On the contrary, the defendant is in no mood to be mealy-mouthed. She is unapologetic, defiant and saying it as she sees it but not even a hint at race is to be found. Indeed there are no abusive words full stop, much less racially abusive words. There is a singular insult in the form of “bastards” but it is non-specific and not connected to any protected group

At least one target race is essential for the offence to be made out; as established as in R v Norwood [2003] EWCA Crim 1983 where a conviction was upheld because the language was unambiguously aimed at a protected class

The occupants of hotels do not constitute a defined racial or ethnic group as set out by Lord Fraser in Mandla v Dowell-Lee [1983] 2 AC 548 in finding that Sikhs constituted an ethnic group based on various shared characteristics. The hotel occupants may and do in fact come from various racial and national backgrounds, no less than five continents, and they speak a plethora of languages. In R v Sheppard and Whittle [2010] EWCA Crim 65, the written material clearly and explicitly targeted racial groups.

The contention may be that racism was the undercurrent or subtext or motivating factor for the defendant’s words but such inference is insufficient and in any event denied. At the material time, the defendant saw the housed migrants as being collectively responsible for the Southport stabbing incident earlier that day - mistakenly, yes - unreasonably, yes - but not on account of race insofar as they belong to an agreed upon race or set of races which they do not. Lord Reid in Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1964] AC 234 (HL), “What the ordinary man would infer without special knowledge has always been the test. He is not naïve; he can read between the lines... But he must base his inference on what the defendant has actually said”

The defendant includes the phrase “if that makes me racist, so be it” which is to say “if the consequence of what I have just said is to be labelled a ‘racist’, then I accept that consequence”. In other words, at the material time, the defendant was not willing to censor herself in order to avoid being called a ‘racist’. There is no admission of racist intent, quite the contrary, she is pre-empting being called a “racist”, conscious of how liberally and often unreasonably the accusation is levelled. Either way, though, the preceding parts of the post do not contain language directed at a race.

The prosecution seeks to rely on adjacent communications, such as other posts she made, in an effort to establish racist intent. This is to concede, of course, whether they like it or not, that the racial element of the alleged offence is lacking. The Court is reminded of the wording of the offence under s.19 (a): he intends thereby to stir up racial hatred, as to say, by effect of the material itself. The Crown must show the words in and of themselves reflect an intention to stir up. General characterisations of the defendant as someone who, say, harbours racist views are not good enough under the test. The court is obliged to assess the allegedly offending words in their own terms without cross-reference to the defendant's speculated opinions on race. In DPP v Collins [2006] UKHL 40, the House of Lords emphasised that the court must assess whether the words used in the charged communication are, in and of themselves, threatening, abusive or insulting, without importing general character assessments. Similarly, in Chabloz v CPS [2019] EWHC 3094 (Admin), it was affirmed that while prior conduct might inform context, the focus must remain on the specific material charged.

Absent at least one discernible target racial group, the offence of stirring up “racial hatred” is not made out. The only coherent charge would have been one of “encouraging or assisting a crime” pursuant to the Serious Crime Act 2007 which it is submitted the Crown knew it could not sustain and so strategically opted for a Public Order offence being the softer test insofar as it does not require proving an intention to cause violence per se. The charge is thus an abuse of process and the court is asked to stay proceedings permanently.

2. No Call to Arms

The key clause is “Set fire to all the fucking hotels full of the bastards, for all I care [my emphasis]”

The insertion of “for all I care” crucially shifts the grammatical mood from the imperative mood (an order or command) to the subjunctive mood. It is no longer a call for arson but an expression of indifference to arson occurring.

“for all I care” is not mere linguistic style. Indignant as the defendant feels at the time of her post, she is evidently unwilling to go as far as issuing a command of violence and so stops short of doing so (and follows this up with a later tweet denouncing violence as being not the answer)

The court is bound by the literal meaning rule. The prosecution is not entitled to rely on paraphrased or isolated parts of the post or to reinterpret words beyond their linguistic boundaries. Charleston v News Group Newspapers Ltd [1995] 2 AC

An ephemeral post does not amount to a “publication”

Consider a company bound by the Companies Act 2006 to publish its annual accounts. It does so by posting a link to a PDF on its website but then 3.5 hours later deletes it and attempts to argue that it has complied with the requirement. This would not wash with any court or regulator in the Land. “Publication” is not satisfied by the mere technical act of making something visible for a short time. Jameel v Dow Jones & Co Inc [2005] EWCA Civ 75: the mere technical accessibility is not sufficient for liability.

In criminal law where freedom of expression (Article 10 ECHR) is engaged, the definition of ‘publication’ must be narrower, not broader, than in a civil context

It is submitted that ‘publication’ requires a defendant’s intention to disseminate the offending words - whatever they may be - to be realised or made effective through continuity of access. Thus an essential property of a ‘publication’ is durability. It’s submitted 3.5 hours is so short a period as for a reasonable person not to accept any publication materialised

Publishing something is not an irrevocable act. It is the prerogative of a publisher to retract or withdraw that which he has published. This is well established convention. Academic journals often issue retractions. The right to revoke a publication is a necessary extension of the GDPR’s Right of Erasure a.k.a. the Right to be Forgotten which would not be satisfied if the ordinary person were prevented from taking back the words he or she has used

The deletion of the post by the defendant is incompatible with the intent required to be proven under s.19 (a) (1) and was also so swift as to disqualify the post from amounting to a “publication”

Views do not equate to “distribution”

‘Distribution’ within in the meaning of Act entails an offender actively and effectively disseminating the offending material or words. This could be handing out flyers as in R v. Bird (1988) or, sending e-mails or text messages, or perhaps recruiting others by word of mouth to attack someone: “tonight, when he gets off work, let’s fuck up John”; but in any event doing something

The prosecution would have the court imagine that 300k views is tantamount to the defendant having handed out 300,000 printed copies of her post which, it is submitted, is a nonsense. After the defendant clicks “Post”, she is but a passive observer. She has no influence whatsoever over the alleged (and unverified) number of “views” and instead is entirely at the mercy of X’s algorithm and the inclination of others to repost as to how much visibility the post eventually gets. In DPP v Collins, the court distinguished between a person's original communication and how widely it spread once in the public domain with the original speaker not being accountable for the latter

In a private message, the defendant talks of the post having “bit [her] on the arse” which refers to the unforeseen negative fallout of one’s actions. The defendant realises she has posted something heedlessly and is expressing consternation at the blowback she is receiving from that action. This is not compatible with an intention to distribute and, by extension, an intention ‘to stir up’. The necessary mental element of the charge is lacking.

The defendant does nothing herself to enhance the visibility of the post. She does not use hashtags. She does not tag anybody. She does not request for it be shared or reposted. Indeed the only positive action she does take is to delete it.

Timing as a mitigating, not aggravating, factor

The prosecution seek to the argue that the prevailing political climate aggravates the offence

This is purely speculative as there is no objective standard as to what constitutes a time of heightened political sensitivity or any way of determining to what extent the social atmosphere is supposedly fraught. There is no barometer to which one can refer. There is no control environment as to be able to say that, had the defendant made her post at a time of relative calm (to the extent such a time even exists), that it would have been less disruptive. Indeed there is no way to say the post had any effect whatsoever much less a measurably worse effect because of its timing.

The argument also works both ways. If a speaker is addressing a gathering which is tense and on edge and which subsequently turns disorderly, you can say, on one hand, the timing of speech made matters worse but equally that tensions were already very high before the speaker arrived on the scene and so the speech is unlikely to have made any difference. In other words, that disorder would have followed regardless.

Consider a road rage incident where a driver is stuck in gridlocked traffic and becoming increasingly frustrated. At a certain point, he loses his temper, gets out of his car and has an angry outburst in the middle of the carriageway which is said to cause alarm and distress to surrounding motorists, giving rise to a Public Order offence. The prosecution argue the large number of motorists on the road at the time aggravates the offence. This results in an absurdity whereby the very thing that has precipitated the offending conduct is also said to have aggravated it, violating the Golden Rule, Adler v George [1964] 2 QB 7.

In the defendant’s case, it is the timing - being the Southport stabbings - that is itself the triggering factor for her post. Unless it is suggested the defendant had a draft of her post saved and that she chose to deploy it at a time when she believed it cause maximum disruption, then she is a victim of said timing, and insofar as she is guilty of the alleged offence (which is denied), the timing is a mitigating, not an aggravating, factor. To seek to hold the timing of the post against the defendant would be perverse and amounts to a cynical attempt to fashion a more serious offence than exists.

The offence is not made out

I do not claim this defence would have succeeded necessarily because, when facing a pre-determined outcome, it does not matter what you say. What I do say, though, is that it could not elude even the most junior barrister of questionable competence that a post that makes nil reference to race is liable to amount to a flagrant abuse of process by the Crown.

It gets worse, though. Instead Lucy is advised to put in a “plea in mitigation”, something intended to excuse the offending conduct and lessen the offence which was not merely unhelpful but positively damaging to her cause. This is not to diminish Lucy’s personal trauma as regards the loss of her child 14 years prior, only to say legally it had next to no chance of succeeding. The event had no proximity to the alleged offence and the judge ultimately had none of it (pa. 21, Sentencing Remarks). I’m not privy to what was in Lucy’s mind at the time and so cannot say to what extent it contributed to her reaction that evening but the perception from a court and the public was guaranteed to be that she was seeking to leverage a personal tragedy to excuse “hate speech”. Apart from anything else, it had emerged that she had said something to the effect of intending to play the mental health card which would have been pretty much fatal to any chance of her getting any mileage out of such a plea. That a barrister would even suggest pursuing this course, one that was sure to seal her fate, is highly suspect.

In closing, I come to some of the commentary in the aftermath of Lucy’s sentence, most of which has not done her any favours in my estimation, and that includes Allisson Pearson’s piece in The Telegraph. I’ve no objection to the title vis-à-vis Britain bearing shame for her injustice, that much is true. It’s when we get into the substance, or the lack thereof more accurately, that problems emerge. I had expected, naively, to find a spirited defence of Lucy on grounds of free speech. I thought I might hear of how Milton, Blackstone, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Paine et al. would all be turning in their respective graves to hear of her plight, but nothing of the sort. Five paragraphs in, Ms. Pearson completely bails on her: “It was without doubt a horrible, hateful and deeply offensive tweet”. We are to take it from that she agrees Lucy committed the offence, only that her sentence was unduly harsh.

How craven. What does it matter whether it was “deeply offensive”? Perhaps a brief refresher on our tradition of free speech is due. We do not criminalise impassioned speech. We do not imprison those who indulge in hyperbole or take liberties with language in the heat of the moment. We do not lock people up for having an intemperate outburst. It’s incumbent upon a journalist to say as much and, if you’re not willing to stick your neck out for fear of being seen to condone an “offensive” tweet, then maybe it’s time to reconsider your chosen profession.

The entire piece is predicated on Lucy’s guilt and amounts to a futile plea for leniency on the grounds she is not a bad person. We know this because, among other things, the dog, Harley, misses her terribly, also, Ray found her crying when he got in, plus, she used to look after some black kids. Apparently this flaccid waffling passes for journalism. I don’t care whether Lucy is a good person nor do I know it be so, frankly. I care only that state-sanctioned entrapment was used to pin a bogus charge of ‘stirring up racial hatred’ on her; and that she was railroaded through the charade that is our judicial system, treated as an expendable nobody, all so the credulous, docile masses would hail the arrival of online censorship. By pleading her good character, the implication is that she might otherwise have deserved such treatment. There are some redeeming parts to Ms. Pearson’s article, notably, references to “informal pressure” from above and the judges needing to “crack down hard” but it’s largely a masterclass in controlled opposition writing. Lucy’s supporters learn almost nothing of value and her detractors come away thinking it’s a whinge-fest.