Letby and the Insulin Cases: Overcoming The First Stage of Grief

(edited 24.05.25)

When you so desperately want something to be true, you’ll let nothing interfere with that belief. So it seems in the case of Lucy Letby’s supporters, thoroughly convinced as many are, that the whole thing is a fit up; that she’s been scapegoated for a deficient NHS, or some variation thereof. The more militant among her advocates are not merely saying her convictions – 7 counts each of murder and attempted murder - are unsafe but in fact calling for her summary release. Others are rather more restrained, however, and remain troubled by (= in denial about) the two counts of attempted murder by means of insulin poisoning: Baby F and Baby L. As well they might be. They form the lynchpin of the case against her forensically. Once you have her on those two, the house of cards comes crashing down and the likelihood that she then did not have a hand in the 12 other instances becomes vanishingly small. Indeed there’s an argument the CPS should have pursued only these two counts in the first instance and, contingent on the verdict, gone for some or all of the others. This would have allowed for a much more focussed trial instead of the 10-month epic it turned out to be - an unfair burden on jurors, in my opinion, whilst also risking much evidence getting lost in a haze.

Legal hobbyists and internet sleuths alike are found on Reddit and elsewhere poring over the intricacies of the insulin test results, straining every sinew to reconcile their desire for this woman to be innocent with what the tests show; that these babies had extraordinarily high levels of insulin in their blood. Not double, or treble, or quadruple, or quintuple; but anywhere between 60-460x the normal level for a preterm neonate (depending on feeding status). Some choice examples of the mental gymnastics I describe (from Reddit) follow:

“I have tbh, the child F result is very unusual and kind of worrying, that I understand why it looks the way it does. It’s very easy to see it as it is”;

“I still believe Letby is a victim of a miscarriage of justice but I can’t deny that’s a hard thing to explain, although not that she’s even done it, but just that the baby has been poisoned by insulin”;

“Whilst I do lean heavily towards this all being a massive miscarriage of justice, I have to be honest, the insulin cases are still very hard to dismiss”

“even if there is categorical evidence of insulin poisoning, given that there is still absolutely no concrete evidence related to Letby, it's not satisfactory for me to bang fifteen life sentences on her head”;

"Again, to be clear, I am personally very invested in Letby being innocent…And like I said, being unable to explain the insulin results doesn’t imply Letby is guilty. But we still lack a robust alternative explanation, other than ‘these tests aren’t entirely reliable’”

It’s very easy to “see it as it is”, he says, as opposed to not how it is? Who are these people? As for being “very invested” in her innocence, if you’re very invested in anything other than the truth, perhaps it’s time to politely and quietly relieve yourself of further participation in the discussion and take up a new pastime, if only out of respect for the parents of those infants who either perished or nearly died under Letby’s care. Your judgement is coloured by a personal agenda. If, on the other hand, you regard yourself a neutral observer who maintains the insulin tests are inconclusive, it’s likely you lack a basic grasp of the relevant biology, specifically the relationship between insulin and c-peptide – one you probably ought to have if you fancy yourself as an armchair expert on this case.

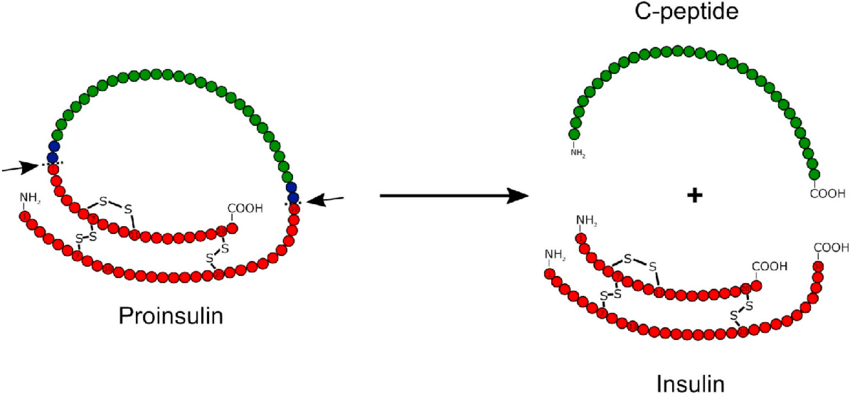

Insulin, as you all know, is a powerful life-critical hormone (protein) secreted by your pancreas which regulates your blood sugar, one of the mostly tightly controlled parameters in the human body, honed to precision through millions of years of evolution. The insulin molecule consists of two chains of amino acids: A and B. It starts out in its inactive, precursor form – proinsulin – where A and B are bound together by a scaffolding molecule namely c-peptide (connecting peptide).

Upon conversion into insulin, c-peptide, shown here in green, is cleaved off (removed) enzymatically and left behind where it remains in the blood and for much longer than its insulin counterpart. It has a longer half-life in pharmacological terms. Synthetic insulin undergoes no such conversion. It’s ready to go.

Just as walking in the snow leaves a trail of footprints, one for each step, so each secreted molecule of insulin leaves behind another of c-peptide. Thus, they jointly increase in the blood in a perfectly linear 1-to-1 fashion. This is an immutable feature of our biochemistry. The process cannot be cheated. There isn’t some backdoor method for your body to make insulin that doesn’t leave behind a c-peptide trail. It is this same feature that makes c-peptide an extremely robust, virtually infallible, biomarker for endogenous (natural) insulin and so by looking at the ratio of one to the other we can reliably deduce whether the insulin present in someone’s blood is natural or not, with caveats to be discussed. Owing to the longer half-life of c-peptide, this ratio will always be >1 under normal conditions, around 1.5-2 in newborns and typically 5-10 in adults (as the half-life becomes longer still). In Baby F, it was <0.036. In Baby L, the values were beyond the respective lower and upper detection limits meaning the baby’s insulin exceeded ~5,000-6000 pmol/L whilst c-peptide was <169 pmol/L, so a ratio <0.034.

Now the crucial part: the interpretation. There are a few rare - very rare - situations in which the ratio of c-peptide to insulin will invert i.e. fall below 1. We will come back to those, don’t worry. The only scenario, however, in which the ratio will violently plummet to near zero is where exogenous (synthetic) insulin has been administered. This is because the standard test (immunoassay) does not distinguish between endogenous and exogenous insulin. At the same time, the pancreas detects blood sugar is low. Natural insulin production is suppressed accordingly. The readings are sent in opposite directions: insulin soars and c-peptide crashes giving the wildly out-of-kilter ratio observed in both cases.

Still not satisfied, Letby’s defenders seek out every esoteric theory in town in an effort to discredit or explain away the tests. The problem is none of them stack up:

“The test doesn’t tell us whether it was natural or synthetic insulin”. Answer: correct, it does not. That’s why it’s paired with the c-peptide as to tell you whether the measured insulin represents naturally produced insulin. It categorically did not in either case.

“It could be hyperinsulinism caused by a tumour (insulinoma) or genetic mutation”. Answer: Hyperinsulinism doesn’t invert the ratio. There’s more insulin but also more c-peptide. In any case, these babies did not have diagnoses of hyperinsulinism. They would otherwise have had, not acute, but chronic hypoglycaemia and we would not have seen blood glucose normalise after disconnection from the IV.

“What about Hirata’s Disease a.k.a. Insulin Autoimmune Syndrome (IAS)?”. Answer: This is an autoimmune condition where antibodies bind to free insulin preventing its clearance potentially leading to a distorted ratio. IAS is virtually unheard of outside of Japan and is not congenital. These babies did not have diagnoses of IAS nor would IAS result in the near-zero ratio observed.

“Kidney failure causing impaired insulin clearance” Answer: Neither baby had diagnosed kidney failure and it would not cause a ratio anywhere near as low. Insulin would have been chronically high without subsequent normalisation of blood glucose after disconnection from IV.

“Paraneoplastic or ectopic insulin-like factor production” Answer: These types of tumours are not seen in infants and insulin would still be accompanied by c-peptide if it’s true insulin.

“Heterophile Antibody Interference” Answer: This is where the patient’s specific antibodies cross react with the reagents in the test producing a falsely elevated insulin reading. Roche incorporates proprietary blocking agents into its assay to neutralise heterophiles antibodies. Nevertheless, no test is perfect and they are not immune from interference. In <1 in 2000 tests interference happens (Sapin et al., 2003). However, the false elevation due to interference is nowhere near the order seen. We’d expect insulin readings in the hundreds of picomoles, low thousands at the most; and it would not affect the c-peptide value. Therefore, a ratio in the order 0.2-0.5, way above what we actually saw. For antibody interference to account for the results in these two babies, you’d need to claim there was a uniquely extreme pattern of false elevation in these two infants, not seen in other babies. This is biologically implausible. It can also be verified retrospectively such interference did not occur by retesting the surviving children’s blood, given that antibodies will generally persist for life.

“They didn’t do liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) testing” Answer: LC-MS requires deep freezing of samples and rapid processing by an equipped forensic lab. It can’t be done in a standard hospital lab. By the time the insulin/c-peptide results had been returned and interpreted, the blood samples would likely no longer have been viable and the insulin in the baby’s system long gone. Therefore, the neonatal team would have had to anticipate the poisoning. Clearly, it’s unreasonable to expect that. In any case, the absence of LC-MS does not detract from what is known which is sufficient to conclude the presence of exogenous insulin.

“The test is not validated for use in (preterm) neonates” Answer: This is proving to be one of the most frequent criticisms demanding rebuttal. It is true, neonates are not merely small adults but a population in their own right with a distinct physiology. Neonatal plasma can differ by protein composition, bilirubin levels and haematocrit. These differences can cause matrix interference (skewed results) in a way that is not the case or at least far less likely in an adult. Certain neonatal phenomena mean reference ranges can radically deviate from those applicable for adults. For instance, there’s a surge in Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) in the first 48hrs of life. Maternal antibodies that have crossed the placenta (which clear after a few months) can also cross-react with the same TSH immunoassay causing false highs. Validating assays for neonates is undeniably relevant and in a clinical setting non-validated tests require cautious interpretation. All of this true; and should Letby ever get her retrial, the prosecution would do well to readily concede as much.

So do we just bin the result, then? No. The question becomes: does neonatal physiology have any material bearing on the interpretation in the context of insulin poisoning? No, it does not. First of all, the target molecule, insulin, is structurally identical in neonates and adults - the same 51-amino acid peptide. The Roche Elecsys® Insulin assay uses monoclonal antibodies that target specific epitopes and those do not change in neonatal plasma making it highly specific and not susceptible to cross-reaction with insulin analogues. It’s designed to work in EDTA plasma or serum which are the same matrices used in neonates and indeed it forms part of routine endocrinology and hypoglycaemia workups in many UK hospitals including for neonates (something those seeking to rubbish the test omit to mention). The fact that no validated assay exists is testament to the fact that there has not been a clinical necessity for one. The test result is not corrupted by using neonatal plasma and is not being used to assert a precise reading. We are not splitting hairs here over, say 50-100, picomoles of insulin, rather using it (in combination with c-peptide) to determine the presence of massive, supraphysiological levels of insulin in two infants. You could grant a 30%, even 50%, upward bias in the reading due to matrix interference. The conclusion would remain because the readings were beyond any conceivable margin of error. Just as if someone were caught speeding, doing in 95mph in 40 zone, doubling the usual allowance of 10% + 2mph, to 20% + 4mph does not change anything.

The test was not abused at trial to say more than it could say and needed to say. Now, if critics were arguing that the prosecution had a duty to declare the immunoassay lacks validation for neonates, that would be one thing. Then both sides can argue the relevance thereof. What they want instead is the test rendered inadmissible and thrown out altogether which betrays their intention. It’s a cynical attempt to deprive a hypothetical future jury of knowledge of the result because they know what it shows and how fatal it would be to Letby’s defence.

By now, a clear theme should have emerged: other causes for abnormal results are possible - that is not denied - but it is the extreme nature of the values observed in Babies F and L, combined with the clinical picture, that allows for said possibilities to be definitively crossed out. We have four boxes ticked: (i) super high insulin; (ii) very low or undetectable c-peptide; (iii) acute hypoglycaemia; (iv) normalised blood glucose after the babies came off the IV.

These two babies were being infused with lethal quantities of synthetic insulin, completely consistent with their clinical notes and were spared only by timely interruptions. You can debate how it got into their systems as a secondary discussion if you want, but that it was there - and for no plausible reason other than to poison them is beyond reasonable doubt, the standard of proof in a criminal trial.

At the Alternative Lucy Letby Trial hosted by UnHerd, Investigative Editor, David Rose, says (19:05) “nobody has satisfactorily explained how on Earth Lucy Letby could have introduced synthetic insulin into feed bags that these babies were receiving through IV lines”. as if this were a logistical feat beyond Letby’s means. I am going to charitably assume ignorance here rather than wilfully trying to mislead the audience. A neonatal IV bag (as for standard adult IV bag) has both a spike or tubing port and an additive port - a rubber self-sealing stopper for injecting medications or other constituents. This is true also for neonatal Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) bags too such as the Numeta® G13E triple-chamber bag from Baxter which I believe will have been the type in use at the Countess of Chester.

These are not the only entry points. There’s also the Y-port proximal to the baby or the cannula hub but those points bypass the feed bag so you would not have a gradual infusion and instead an IV bolus where the medication is administered all in one go. Lastly, a syringe driver if one were in use which was the case in one of the babies, as I understand it.

Bolus administration does not fit the clinical picture. Giving that much insulin in one go would have caused rapid collapse, almost certainly death, within minutes, attracting considerable suspicion. Infusion allows for the appearance of deterioration overnight. The babies had persistent hypoglycaemia over a period of many hours which crucially resolved after discontinuing the infusion. Insulin has very short half life of only a few minutes, indicating the poisoned infusion was either ongoing when the respective blood specimens were collected or had just been stopped.

How much insulin would she have needed to introduce to the feed bag? Keep in mind the tiny and fragile nature of preterm neonate weighing 2-2.5kg with less 1/2 pint of blood. Insulin comes in U-100 form: 100 units/ml, 6,000 pmol per unit. To cause a steady-state plasma concentration of ~5000 pmol/L there are various pharmacokinetic variables to account for: dilution ratio of the TPN bag, volume distribution (Vd) for insulin in neonates (~0.15) which means how extensively a drug spreads beyond plasma, insulin half life, the infusion rate (typically 3-8ml/hr). The mathematical formula is beyond the scope of this piece but anywhere between 30-60 units of synthetic insulin or 0.3-0.6ml is a reasonable estimate of how much Letby would have had to have added.

Insulin tends to stick (adsorb) to plastic surfaces and so ideally will be well mixed and the tubing flushed (primed) as to saturate the inner surfaces with insulin first. This is not a small detail. Proper mixing and flushing makes a significant difference to the effectively infused dose. We can’t know whether Letby took these steps not least because she denies the crime. Let’s assume not and favour the upper end of our estimate. You can play around with the calculation. Whatever the figure, we’re talking about a very small amount of liquid, injectable in a matter of seconds into a feed bag.

Let’s be clear, poisoning a baby with insulin, late at night with only one other staff member on the ward, is not a crime requiring great ingenuity, planning or skill. Just intent, opportunity and a modicum of technical know-how, all of which Letby possessed in her capacity as a neonatal nurse. Christopher Snowdon (whilst I agree with many of his points) refers to her as a “very clever woman”, adept at lying and also “very good in the witness box”. No, this is someone of ordinary intelligence, a criminal mastermind she is not. Granted, she took some precautions to be avoid being caught in terms of falsifying records but not more than that. On the contrary, many of her actions are quite reckless. Using her phone to do Facebook searches of the parents on the anniversaries of the children’s deaths and stashing handover notes under her bed, come to mind. Her performance in the witness box is hardly impressive. When forced to account for the many irregularities that emerged, she can’t and reaches for her preferred stock answer: “No, I don’t agree”.

It was not a careful campaign of deception that allowed for Letby to evade capture for as long she did but a culture of complicity and timidity shielding her from direct accusation. Her fellow nurses and senior management had her back, fending off doctors’ concerns, principally Dr. Brearey’s, as to avoid making waves. Entirely self-serving, of course. The doctors relented albeit with misgivings, on my reading. (This internal friction between the professions was a significant feature and warrants inquiry in its own right).

In Letby, I ultimately recognise simply a deeply disturbed young woman who abused her position of trust in the most horrific way. Her handwritten confessions reflect a state of genuine mental turmoil, being wracked with guilt. I believe it’s possible to feel justified pity for her in spite of her appalling deeds. What is not an option, however, is to cling in vain to a notion that she’s innocent in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, therein lies my appeal to her more thoughtful supporters.

A correction. Child L's insulin was recorded at 1,099 and C-peptide as 269. Prof. Hindmarsh described the insulin level of 1,099 as a minimum, not a maximum, because the time at which the blood sample was taken was in dispute. The prosecution argued it was taken around 3:30. The defence said it was taken earlier, as recorded by Dr. Mayberry's retrospective notes.

Child L's poisoning also continued after the final offending bag was disconnected, as the insulin had stuck to the giving set.

Split hairs aside, fantastic piece.

Oodles of psychological projectin of Phil's part as he describes Letby 'supporters' as desperate etc.

Others commentators have gone into great details about his faulty reason with regards to the science.

I would just like to ask: so how much insulin wuld she have needed to injedct. And why was none reported to be missing?